Winter on the Edge - Glacier National Park - East Glacier Park, Montana

Winter on the eastern edge of Glacier National Park, in the small town of East Glacier Park, Montana, is known mainly to the few people that make this place their home, and a few travelers. Life in East Glacier Park is nothing like life in the more well known and often cited West Glacier (the headquarters of Glacier National Park). The wind blows more, it's colder, winter lasts about two months longer, and there's always more snow! That's a good thing if you like snow.

Recent study's indicate that about two million people visit Glacier National Park, Montana each year. People from all over the world travel to Montana and Glacier National Park for vacations and many of them travel though East Glacier Park, Montana. When people come to Montana it changes them.

I hear stories all the time about people affected by their time spent in Glacier National Park and in East Glacier Park specifically. I talked to one person last year who was working as temporary employee for the National Park Service who said they love the place so much they decided to stay for the winter. I replied with a question, "Where are you from?" Most are not use to long, hard winters in deep snow and often don't last long in East Glacier Park, particularity after spending one winter here.

The long winters are brutal on people who prefer warmer temperatures! There's often snow in yards starting in September and finally melting in late May and sometimes into early June. I hope that some of you will recognize a few of the locations shown in the photographs and in the slideshow.

I’ve been thinking about this blog post for a long time. I’ve always wanted to share the sights of winter in East Glacier Park. I finally got it together and made it happen.

This post really is for those that love East Glacier Park, and Glacier National Park, but who only ever see it when it’s green and warm! Please enjoy the photographs and the slideshow with images of snow and ice in East Glacier Park, Montana. Please share a link to this post with anyone you think would be thrilled to see East Glacier Park in the winter, or those who you think don’t really know what snow looks like!

Have you ever been to Glacier National Park in the winter?

Stay warm out there! Tony Bynum

Simple tips to improve your outdoor photography - take more outdoor photographs - 5 tips

The secret to good outdoor photographs starts by taking more of them! Consistently good outdoor photographs are the results of practice, hard work, and a commitment to a goal. Make this years goal be, take more outdoor photographs!

Outdoor photography to most means nature photography. Wildlife, landscapes, etc. But, outdoor photography can be any photograph taken outside or even taken from inside of an outside environment!

Here are five simple tips that will help you improve your outdoor photography. They ONLY work if get out and take more pictures!

1. Keep your horizons level. Outdoor photographs of natural places look horrible with slanted horizons. . .

2. Eliminate distracting elements. Watching the edges of the frame. Don’t let that one blade of grass or stray branch ruin an otherwise great photo. You may have to find a new position, adjust your focal distance, or remove the item from the scene. Be judicious about moving things. I support some modest changes but I won't move a tree . . .

3. Use shadows. Outdoor photographs should have some shadows. Find sidelight to help improve shadows and give depth to your outdoor photographs.

4. Use a human. Put a person in your outdoor photographs to give scale and depth.

5. Combine Elements. Use two or more strong elements to help tell a story.

Bonus tip: Don’t drink out of aluminum water bottles when it’s 20 below! Just Say’n.

Good Luck out there,

Tony Bynum

Professional Outdoor Photographer - is there a future for professionals?

Is there a future as a professional outdoor photographer? As a professional outdoor photographer, I think about the future of outdoor photography, and where the art or profession is headed as a way to make a living. I'm asked questions like, "aren't you afraid that you wont be able to make money," and "what about all the competition - everyone has a camera these days and are literally giving away their photos just to see their names in print - doesn't that worry you?" Another common one, "what do you fear most about the future of your profession." People are assuming that the profession of photography is dying due to lower barriers to entry, more free time, more people with more money, and the improvement in technology, not to mention the changing culture and the fact that today's younger generation want what they want, and they wont be guided by rules and constraints. . .

So here's my answer. It's always the same, "I'm worried about my health (I'm not sick, but as our bodies wear out, it's harder to stay on top in the outdoor photography world), motivation to keep going, and ultimately my happiness." I don't spend time worrying about what other's say, do, or publish. I don't worry about the prices I'm paid for my hard work dropping though the floor. I'm in competition with myself to do the best job I can and make certain that everyone of my clients is taken care of. In other words, I just do what I do, and let the chips fall where they may.

So, why am I writing this? I'm writing this because I read a great article about photography and the new generation, and I absolutely loved it! I wanted to share it with my community of photographers.

The future is exactly where the past has been. Moving forward. Inventing newer, faster, smaller, better ways of visually communicating. The profession will leave behind those that can't or wont adjust. There's no stopping the momentum.

To me it's like a wave. If you're surfing, you're either paddling out and over the wave, riding in front of the wave trying to get enough speed to actually ride the wave (get on top of it), or you crash . . . I feel like I've always been paddling in front of the wave but never really been on the top - "owning it," so to speak. . . As good as some of my work is, (I'm not back slapping, I'm acknowledging hard work,) I still feel like I'm never "killing-it." The younger generation does not worry about "killing it." They "kick-it." They grow their hair out like we did when we were kids and I swear if I had my Welcome Back Kotter (I hope some of you remember that show) t-shirt that said, "up your nose with a rubber hose," I could sell it to one of these kids for a mint! That's just the way things are going . . . No restrictions, and no boundaries. The rules are blurry and becoming more blurry by the day. The younger generation is not compelled to follow the traditional process or get stuck in the quagmire of some sophisticated system of becoming an artist, they just do it!

The future of the professional outdoor photographer is positive. There is a future in it for those who are willing to embrace change learn to live the lifestyle . . . So, embrace the future. Move with it not against it. Ride the wave but better yet, skip "killing-it," and go right to "kickn-it."

If you're into photography, or philosophy, read this pieces by Kirk Tuck, I think you'll like it! Here is the link to Kirk Tuck's article,

The graying of traditional photography and why everything is getting re-invented in a form we don't understand.

Where do you think photography is headed? What are your challenges?

Sincerely,

Tony Bynum

P.S. Check out this great interview with Maury Postal if you want the "big-shot's, take on professional photography, it's worth the read http://www.pdnonline.com/features/Social@Ogilvys-ACD-9327.shtml

Nature Photographs - 10 musts for consistently good Nature Photographs

If you want to consistently capture great nature photographs, the following rules apply. . .

- Great Nature Photographs come from getting up early and/or staying late - not even Photoshop can make this rule go away.

- You must use good technique and quality lenses.

- Great Nature Photographs mean you can't be afraid of or dislike bugs.

- You must be willing to travel, and sometimes all night.

- You must be able to adjust to changing environmental conditions.

- Great Nature Photographs require that you sleep less.

- You must sometimes come home with an experience, a sore body and tired legs.

- You must be able to be disappointed - a lot!

- You must do some things that no one else will.

- Most of all, great nature photographs come when you are in the moment and having fun!

Do you have any "must's" to add for great nature photographs?

Sincerely, Tony Bynum

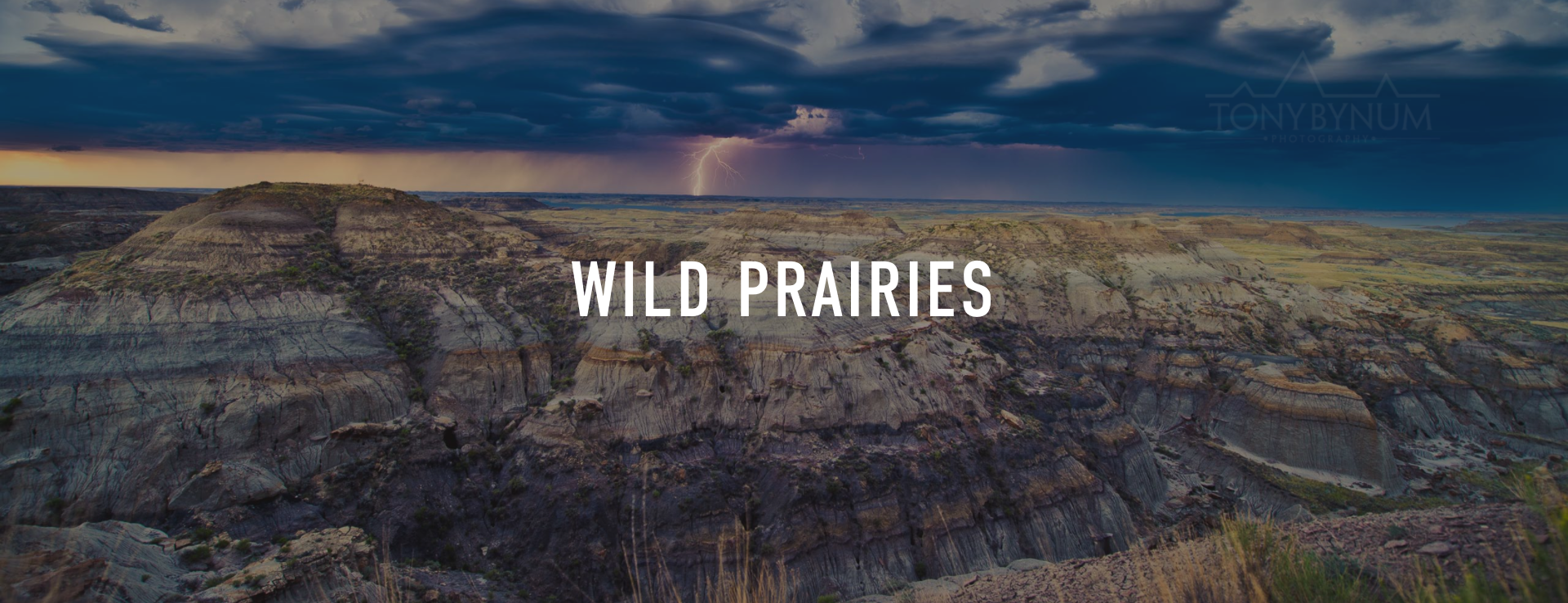

Big Skies and Badlands - Photographing Eastern Montana Lightning

Every year I make time for a trip or two to the badlands of Eastern Montana. The badlands are located where you find them - meaning you just have to tour around until you see them. Why, because I'm not even sure what badlands are these days. I mean, it seems that at least in Montana if something is a badland it inevitably must have some good land mixed in with it - right? So to the best of my knowledge, the "badlands" part is the steep sided, highly erosive, clay soil areas found throughout the eastern and central Montana prairie lands. The areas you can't really ride a horse through, or drive a pickup in, especially if they're wet! Don't argue with me, I know some of you will say, "I could ride MY horse across that country," and some of you would be "right," but in general, these areas are difficult to cross on foot and in most cases you'll need to park your horse. Here's a photographic example of the badlands of Eastern Montana taken near Fort Peck Lake. This photograph is one of my favorites from this summer's adventures. After spending about 40 days on the road shooting and studying the land and it's critters, and watching countless clouds build, spill rain, and blow by, I finally wound up in the right place at the right time with the right conditions to capture an interesting photograph.

There are countless fantastic subjects to photograph under the big skies of Montana. I particularly enjoy photographing the badlands when I find them. I also like the areas I find in between those badlands. What do we call the areas in between the badlands, are they the good-lands? Hum, I'll explore the areas in between in my next post.

For now, remember to keep a safe distance from lightning. Lightning strikes do kill people every year.

Tony Bynum

Glacier National Park, Wild Goose Island Time Lapse

On Saturday, June 9th, I finally made good on a conservation donation I made almost a year ago. Back in September I donated a day with me photographing nature to the Glacier-Two Medicine Alliance. The purpose of the donation was to help raise money for the organization and help it reach it's ultimate vision, "A child of future generations will recognize and can experience the same cultural and ecological richness that we find in the wild-lands of the Badger-Two Medicine today." Fitting! Based on the request of the person who purchased the auction item - me for a day - we headed into Glacier National Park. Our first stop on that mostly cloudy and rainy day, as it turned out, was Saint Mary's Lake, and Wild Goose Island. That location is best photographed in the morning. As I was learning to photograph Glacier National Park, I once drove back and forth from Browning, MT where I was living at the time, to Saint Mary Lake 25 times over the course of 25 days just to photograph it. However, on this outing we have only one day to get it right!

As luck, or fate, since we've been good would have it, we got great light and great clouds. As I was working with my new friend, I set up another camera to capture the scene over the course of about an hour. This is a time lapse of the clouds blowing over Saint Mary Lake, and Wild Goose Island in Glacier National Park.

I like the look of time lapse, particularly when there's some motion. Notice the trees, the lake and the sky. If you want to change it up a bit, try some time lapse, it's really fun!

Remember if you're a Facebook user, you can find me Tony Bynum Photography on Facebook where I post new photos almost everyday!

Cheers!

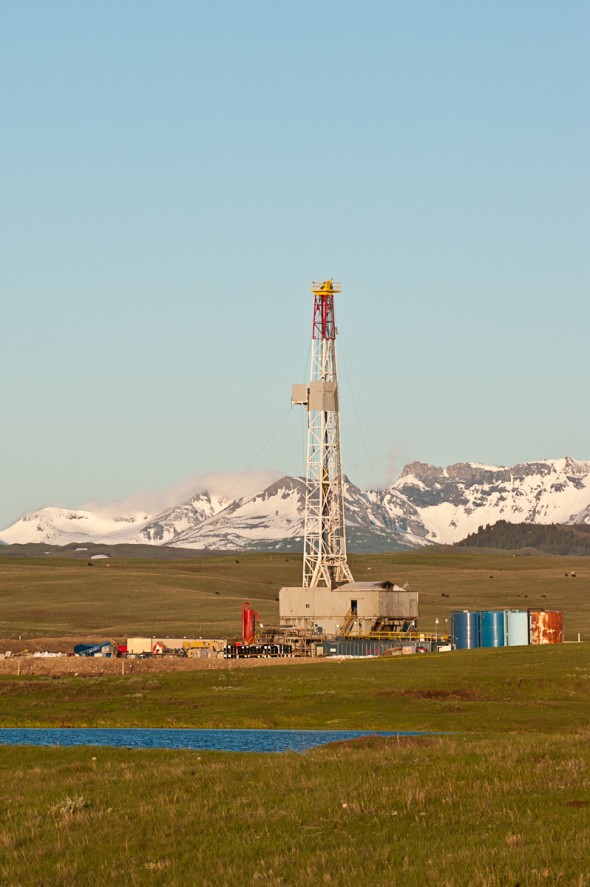

Oil Drilling - the Rocky Mountain Front and Blackfeet Indian Reservation

Wide open, roadless spaces, wildlife, and the people who depend on them and energy development along the Rocky Mountain Front: A Photo Record of “Progress.”

“Documenting current conditions on the Blackfeet Reservation and Rocky Mountain Front today is a very high priority. The landscape, Native American cultures, small towns,

sensitive and endangered wildlife and their habitat, are part of this complex puzzle and being altered at alarming rates.” - Tony Bynum 2010

Introduction, Setting and Scope The eastern front of the northern rocky mountains in Montana and southern Alberta occupies the interface where grizzly bears still freely move back and forth between the mountains and the prairie, is on the brink of massive change, particularly along Glacier National Parks east side. An interactive map of the current oil drilling on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation will help orient you. The eastern side of the crown of the continent ecosystem starts at the sharp jagged peaks in Glacier National Park, Waterton National Park in Alberta, CA, and the Rocky Mountain Front of Montana, where water flows to three oceans and literally divides the east and west. This area was known to the Blackfeet People as the Backbone of the World. More recently it has come to be included in a larger region known today as the Crown of the Continent ecosystem. The geographic region of concern stretches about 150 miles north to south, and 100 miles east to west. It includes the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park, the Rocky Mountain Front, the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, and southern Alberta, Canada.

The focus now is on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation simply because that is where all the activity is now occurring. The Blackfeet Reservation maintains a rich, rare, and relatively intact system of short grass prairie, and associated wildlife, along with the steep jagged mountain ecosystem of the Rocky Mountains. In addition to the prairie-mountain landscape, the Blackfeet Indian Reservation supports a unique Native American and mixed non-Indian culture that is sure to see change as the demand for energy increases, and the oil boom progresses.

The driving force for change is the global, relentless demand for energy. In many ways, this force is impacting every system on earth, not only biophysical systems but social as well. In some real ways, the industrial oil complex holds the keys to the fate of the planet and its inhabitants. The “oil-boom” has reached this land. The industrial oil complex is already solidly established on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation and in the lands to the north in southern Alberta, Canada. The Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park shares a common border with the Blackfeet Reservation.

Oil and gas infrastructure development and wind turbines around the Blackfeet Reservation, and in southern Alberta, are expanding rapidly. Development of both resources is expected to increase markedly though the coming years. Full build-out is expected to be hundreds of new oil wells and pump-jacks, acres of wind turbines and associated infrastructure consisting of hundreds of miles of new roads, work camps, and support facilities which may including new hotels, and associated structures. Estimates are that 100-700 wells will be drilled over the next few years (12 wells are complete already with many more scheduled). Changes to this area will be unprecedented. It is not possible to know in advance exactly how the changes will play out in this setting. Still, there are enough other “oil boom” cases to safely assume they will be dramatic.

Importance of this project At this moment an opportunity exists to capture for educational and historical purposes, images of this mostly healthy, open and “intact” place. Today, we can still document the rapid transition of this cold, short grass prairie. There are progressively fewer such opportunities anywhere in the world. Such an opportunity not only is rare, it is perishable. All too commonly, journalists are in the position of creating the story after the fact, when the “good stuff is gone.” Here there is a rare opportunity to capture images of important landscapes and people before impacts occur. In this area, we still have a relatively intact mountain/prairie interface ecosystem that is home to grizzly and black bears, bull trout, Canada lynx, elk, deer, bighorn sheep, mountain goats and other elements all destined to change.

I want to emphasize that documenting current conditions on the Blackfeet Reservation and along the rocky mountain front today is a very high priority. Native American cultures, small towns, sensitive and endangered wildlife, open and un-tattered ecosystems are part of this complex puzzle and being altered at alarming rates.

The Local Aspect Small, rural communities in remote areas experience firsthand the most direct effects of commercial energy development. The Blackfeet have been on this particular landscape for at least 12,000 years. It now is a remote, mostly intact, relatively peaceful, Native American Reservation. It is the Blackfeet Nation. Now, that Nation appears to face a major energy boom and likely bust as the area changes to become an industrialized tapestry of roads, pump-jacks, evaporation ponds, cars, trucks, houses, stores and whatever else goes with it. At a minimum, it seems certain that once the fields are fully built-out, not only will the land not look the same, it’s people will never again behave the same. This project will document and share images of this landscape and its people before, during, and after the build-out of an intensive, high-cost, industrial energy system comprised of wind turbines, drill and “fracking rigs,” new roads and facilities, along with other associated activities and change. Already, some images of current conditions have been produced in anticipation of this larger project. They form the beginning of a vital baseline that must be established before the land and the people are dis-aggregated, the roads are constructed and the land, water, and wild grizzly bears become scarcer or worse, memories.

The anticipated time frame for my project is 2010-2020. Filming is already underway with about two years completed. The first images are of a relatively intact landscape followed by photos of “progress.” Drilling, drillers, the local economy and the social impacts over the lifetime of the project will follow. The photographs will be used now to help educate people about this threatened region. At the same time, the project will build a digital archive for future generations who can better understand what the land looked like before and during the period of disturbance. Both digital and print images will be created and widely shared with organizations and the public though online media, social networks, web blogs, and personal presentations. Once the road’s are in, the well pads created, the drill rigs erected, ponds dug, the power lines strung and the turbines begin churning, the current largely unobstructed landscape will be a memory. Memories are all that is left when you no longer can see something in person. Images sharpen and stimulate memories. Images are likely to persist through longer spans of time and are more dependable than memories.

The anticipated time frame for my project is 2010-2020. Filming is already underway with about two years completed. The first images are of a relatively intact landscape followed by photos of “progress.” Drilling, drillers, the local economy and the social impacts over the lifetime of the project will follow. The photographs will be used now to help educate people about this threatened region. At the same time, the project will build a digital archive for future generations who can better understand what the land looked like before and during the period of disturbance. Both digital and print images will be created and widely shared with organizations and the public though online media, social networks, web blogs, and personal presentations. Once the road’s are in, the well pads created, the drill rigs erected, ponds dug, the power lines strung and the turbines begin churning, the current largely unobstructed landscape will be a memory. Memories are all that is left when you no longer can see something in person. Images sharpen and stimulate memories. Images are likely to persist through longer spans of time and are more dependable than memories.

To document the entire build out over the coming years I plan to photograph the story from both the land and the air, and with both stills and video. I will follow and record a few specific people as well. I'll shoot and post/publish regularly in order to generate and maintain interest. The campaign will be driven both online and in person. As is so effective today, social media: for examples, Twitter, Facebook, Linkedin, will be an important vehicles. I will employ my personal network along with the much larger network of the people and conservation organizations who care about this place and project - basically everyone who pays attention to natural ecosystems, and likes cowboys, Indians, wildlife, and glaciers.

Cost of this project for year one and two is estimated to be $40,000. The costs include expenses for local travel, fixed wing airplane rental, assistance in the field and office when necessary (mainly web design and development, and continued costs for hosting and management), some special equipment including a ground based radio controlled aerial platform. The aerial platform will enable me to capture low level aerials that offer a better perspective of the relationship between the development and the landscape. It will also be more cost effective, and I can react to local weather conditions and shoot aerials without always the need for a fixed wing aircraft. The remainder will pay for time to capture, process, market and produce the project.

About Me

Education, Science and Business Tony lives in East Glacier Park, MT on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation with his 9 year old daughter. He has more than 20 years of professional and executive environmental management experience. He holds a Master's of Science in Resources Management degree, an undergraduate degree in Geography and Land Studies, and a minor in Environmental Studies from Central Washington University. Tony has managed more than 30 complex scientific research projects for the Environmental Protection Agency from coast to coast, he’s worked in the private sector and for Indian Tribes and non-profits. Over his 20 year professional science career he has participated in the development of countless environmental policies and/or regulations from the EPA, to the USFS, BLM, DoD, DOE, BOR, Washington State’s DOE Wetlands mitigation banking regulations, air and water quality plans, and more. Tony’s a board member of the professional outdoor media association, the East Glacier Park School Board, and a current member and former officer on the East Glacier Park Volunteer Fire Department and a principal member of the Glacier Two Medicine Alliance.

Tony lives in East Glacier Park, MT on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation with his 9 year old daughter. He has more than 20 years of professional and executive environmental management experience. He holds a Master's of Science in Resources Management degree, an undergraduate degree in Geography and Land Studies, and a minor in Environmental Studies from Central Washington University. Tony has managed more than 30 complex scientific research projects for the Environmental Protection Agency from coast to coast, he’s worked in the private sector and for Indian Tribes and non-profits. Over his 20 year professional science career he has participated in the development of countless environmental policies and/or regulations from the EPA, to the USFS, BLM, DoD, DOE, BOR, Washington State’s DOE Wetlands mitigation banking regulations, air and water quality plans, and more. Tony’s a board member of the professional outdoor media association, the East Glacier Park School Board, and a current member and former officer on the East Glacier Park Volunteer Fire Department and a principal member of the Glacier Two Medicine Alliance.

Tony owns Tony Bynum Photography & Glacier Impressions Gallery. In 2004 Interior Secretary Gail Norton appointed Tony to the Montana Resources Advisory Council (federal advisory committee, member 2 years, chairman 1). During that time, from 2005 until early 2010 he also managed complex scientific research projects at Portage, a private consulting firm. From 1999 to 2001 he was a special assistant and the acting Senior Indian Program Manager at EPA in Washington, D.C., responsible for a $2 Million budget, implementing federal statutes, strategic planning, GPRA reporting, and federal rule making. In 1997 and 98 he was the co-chair of the technical oversight committee of the Western Regional Air Partnership.

Bynum’s images have appeared on the covers and in copy of many of the countries major traditional outdoor recreation focused magazines, including Field & Stream, Outdoor Life, Sports Afield, Fair Chase, Texas Sporting Journal, Eastman’s Hunting, and Eastmans Bow hunting, Bugle, Bowhunt America, Montana Outdoors, Montana Magazine, Western Hunter, Western Horseman, and many more. Tony recently became the photo editor for Elk Hunter Magazine and In 2010 he was selected to produce commercial advertising images for the State Of Montana’s Office of Tourism. His images are currently display on buses, trains, billboards, windows, skylights, and elevator doors from Chicago to Seattle, WA.

His list of publication credits is extensive including other industry publications like, National Geographic, the NewYorker, The Food Network Magazine, Popular Photography, Digital Photographer (UK), Delta Sky, Empire Builder and many, many more (complete list between 2009-2011).

Tony’s often hired to produce unique, compelling, thoughtful images to compliment editorial writing in magazines and books. He has worked or traveled to all of the lower 48 states, Mexico, and much of Canada, and writes regularly for his blog. He’s active on Twitter, Facebook, Linkedin, Behance, and moderates and edits photography, outdoor activities and hunting forums on several very popular websites.

Current Interests and Positions 1. conservation photography and the Rocky Mountain Front 2. board member of the Professional Outdoor Media Association 3. board member of the East Glacier Park School District 4. member and past training officer on the East Glacier Park Volunteer Fire Department 5. principal member of the Glacier Two-Medicine Alliance. 6. Author of the blog, www.glacierparkphotographer.com 7. regularly consults with the TWS, the Montana Wilderness Associating, the Montana Wildlife Association, the Coalition to Protect the Rocky Mountain Front, and many other state and national conservation and resource management organizations/groups.

Personal Commitment Central to Tony’s lifestyle is giving something back. As a young man he decided that giving was an essential part of his core belief. To him, giving is a lifestyle choice; it’s more than a duty. There are few things more rewarding or more valuable than offering yourself up to help others. If his entire life were mapped topographically, the ridges would represent the edges of his experience, while the blue line in the valley bottom would signify his giving; it’s central to his life and like the river at the bottom of the valley, all things run though it.

Tony has a unique, and truly authentic set of real-time, current and tested skills in business, management, governance, science, writing, communications, technology, social leadership and teaching. He’s a trained facilitator and has served on three boards where consensus was the agreed processes for decision making. He’s an educator, a leader by nature, a father, and a great friend.

"In the end we will conserve only what we love. We love only what we understand."

- Baba Dioum

A Blackfeet Oil Drilling Press Kit containing project information and photographs to accompany your story is available.